I went back to New York with no money after a few more years or so of eking out survival playing music and working in a falafel stand. I left suddenly. Broke up with the belly-dancer I sometimes lived with. A ton of self-doubt telling me I couldn't possibly be the musician needed to make the music I heard in my head. I decided I would look better as an old writer than as an old white jazz musician.

I went back. I had my notebooks, two changes of clothing, a thick white wool sweater and an old brown bombers jacket. I was 24. I was a wannabe cultural anthropology student, lapsed marine biology student with a B.A. in English lit and a minor in creative writing. If I wasn't going to teach it meant nothing. My first job was selling the New York Times over the telephone still wearing my Mexican poncho. Still about tribal artists and self-taught artists I did not know a thing.

I lived in a roach-infested walk up in Hells Kitchen thinking that if I left he building without seeing a corpse on the stoop it was a good day. I wrote a lot. I went to every jazz club I could afford. Pharoah Sanders, Sam Rivers, McCoy Tyner, Sonny Rollins, Abdullah Ibrahim, Art Ensemble of Chicago, weather Report, Cecil Taylor. So much of it. So rich.

And then I met this woman.

This is not an autobiography. This is a love story. This is the story of a threesome. Shari, me, and a gallery. I am trying and have tried to include only what led to where the gallery is today in our chosen way of life. It is a document about how one can look back retrospectively and see that perhaps there were fewer choices than one would like to admit. That we both (Shari and I) did this dance with chance and opened a Pandora’s box of incredible knowledge and involvement that will never stop offering up its infinite jeweled contents.

You might say we just didn’t know when to stop. I look at what has yet to be written; travels in the US, Mexico, Jamaica, Haiti, Paris and find it daunting and thrilling. So it becomes an autobiography of a journey through amazing art, not a journal of mundane experiences.

I write this because right now this field is at that point where it is more chaotic and more raw and more exposed than ever before. Its earliest participants are no longer alone as new generations of scholars, artists, collectors and dealers come in, some with no idea of the real roots of the material they are working with. This field was built around artists, the artists make their works for whatever their non-mainstream intentions are, and we have built this infrastructure around it. Ours certainly is not the only story. We have always had to see ourselves as some kind of activists. Restless, uncomfortable with labels, pigeonholes, and flagplanting. And now I guess we are old enough to see a thread and a timeline and the regime changes that come with a concept too large to define or contain. We remember when it was adamantly called 20th Century Folk Art, a label militantly defended by some. We are seeing this creep back in again. Collateral damage of failing to define it goes on today as people bend over backwards to stuff something timeless into the arena of Contemporary Art without its own differentness. We are not innocent of some of these mistakes, certainly.

But this art is as much about the process of its being made including the need for it by the maker as it is about the end result. It is not static. And in the spirit of that thought I began to see that our aesthetic and intellectual path of receiving and understanding this work was also a journey of process. We are conceptual midwives. We look back in this memoir and see there was definitely a path we did not even really know we were following.

This is a memoir of receiving information from an ethnosphere, as Wade Davis called it. Of undying admiration for those artists and collectors and others who have stayed on course over the years. It is about wonder. It is truly the intimate susurration of the Wind between the Trees.

Shari’s first real present to me was a box of books about ethnography and tribal art that she bought at OAN bookstore run by the wonderful Linda Cunningham. It was the seed of a library that now sprawls over its own room at the gallery, its own room at our loft and fills book case after book case throughout. We love the feeling of browsing in our own library. I remember that feeling of going through those first books. That there was this astonishing world about to open, that everything was so rich and endless and erotically compelling. And that we two, matched on so many many levels, were about to enter it together.

Ironically Shari and I were both at UCSB at the same time but did not know each other. The conga player for my band which was called Fumando, played for her dance classes where she taught after receiving her MA. She saw the posters for my bands. We did not meet till New York. I was seeing a couple of her room mates and wound up often sleeping on the futon in the living room because they all , with the exception of Shari, kind of had a hive sleeping in one room of a sixth floor walk up on East 53rd Street right dead center in chicken hawk alley. I used to get jeered for being straight on the street outside when I visited. Shari was a waitress at the infamous Hippopotamus disco where chicken C.E.Os (the clucking kind) would come in after hours with hookers and the floor was crunchy with spilled cocaine. She would get home sleep for three hours and on waking I would be the only one home and she would make me espresso. Then she would go dance all day.

One time she went to visit her family and boyfriend in California. I kind of remember this a bit abashedly but with an evil grin. While she was gone I moved into her room. She never kicked me out.

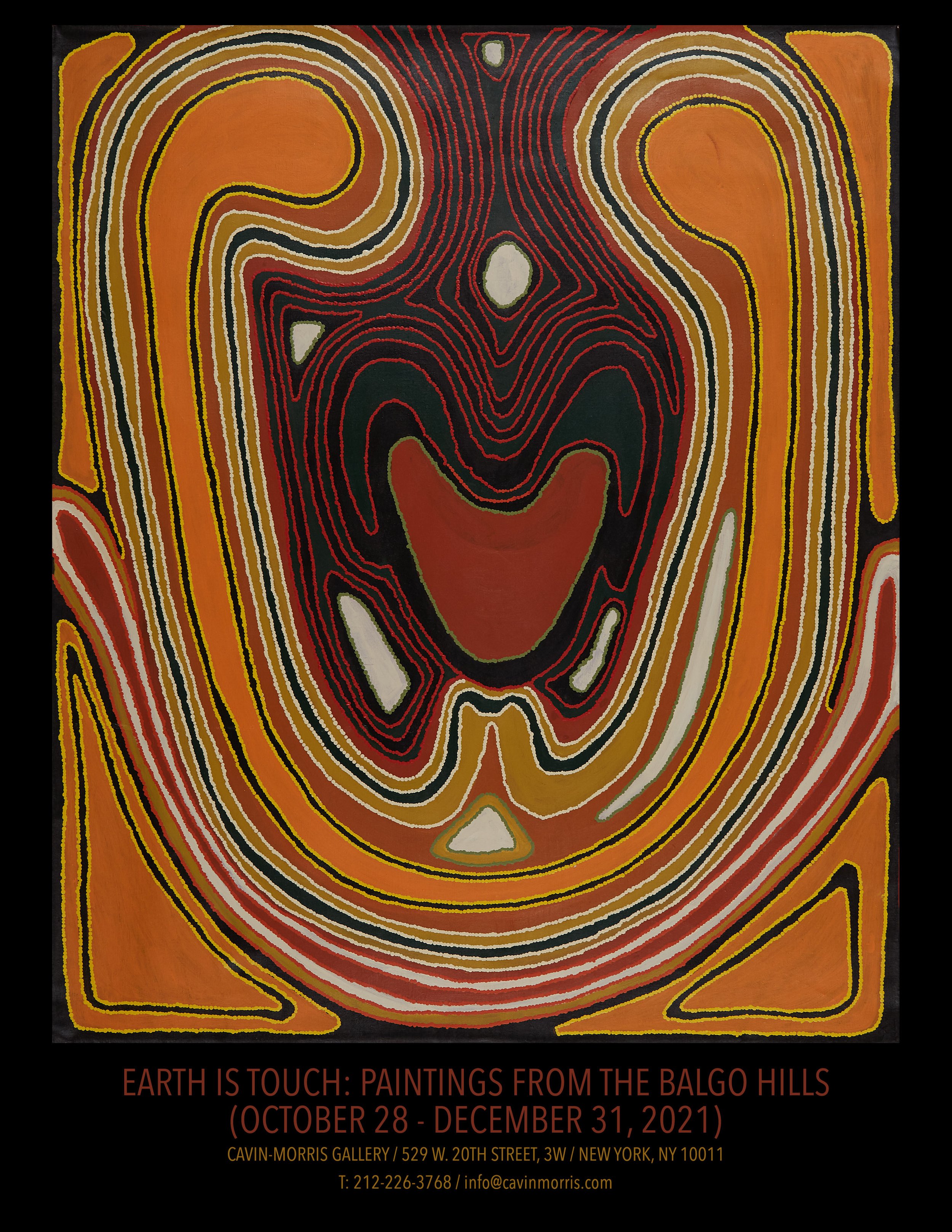

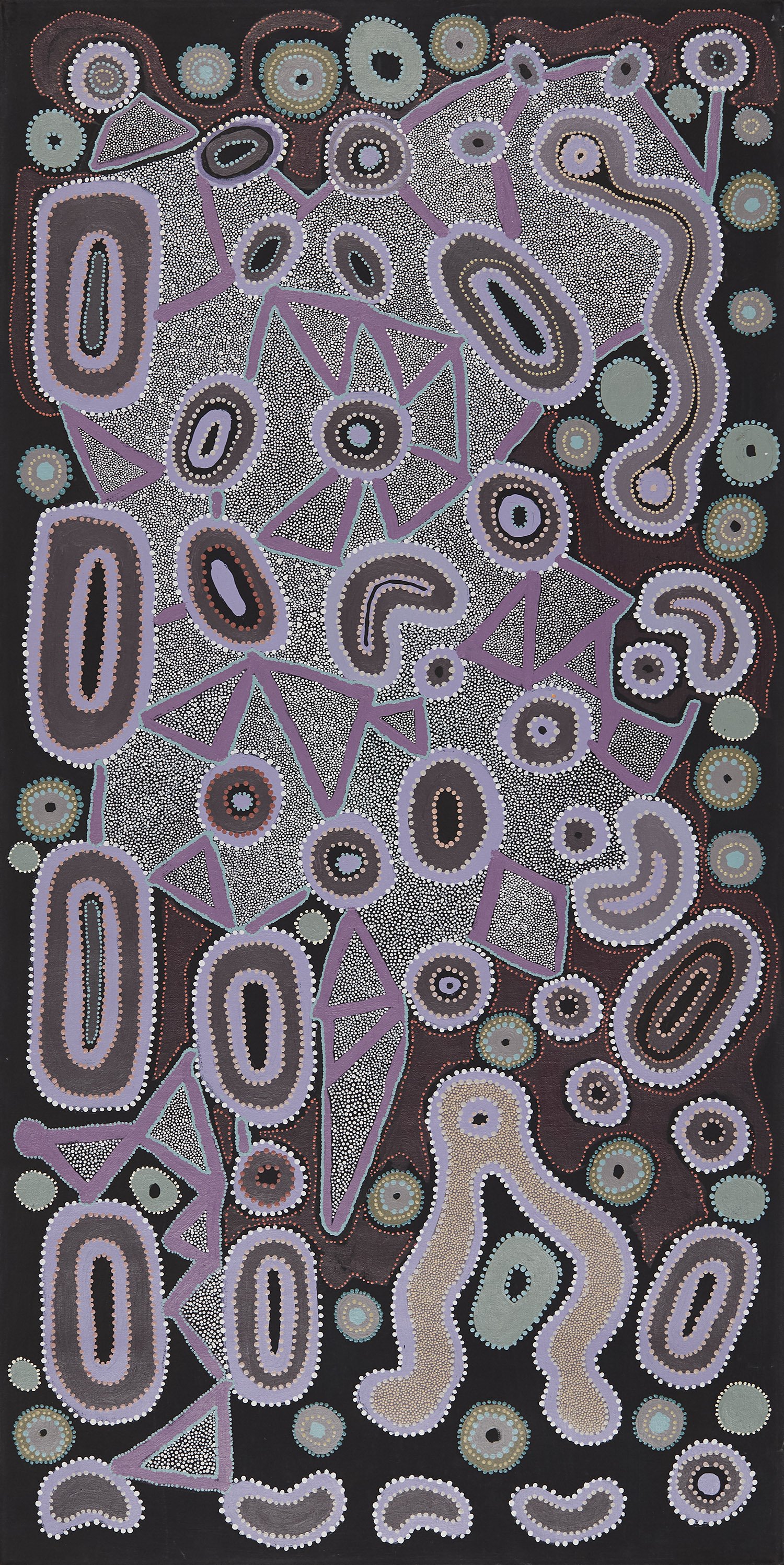

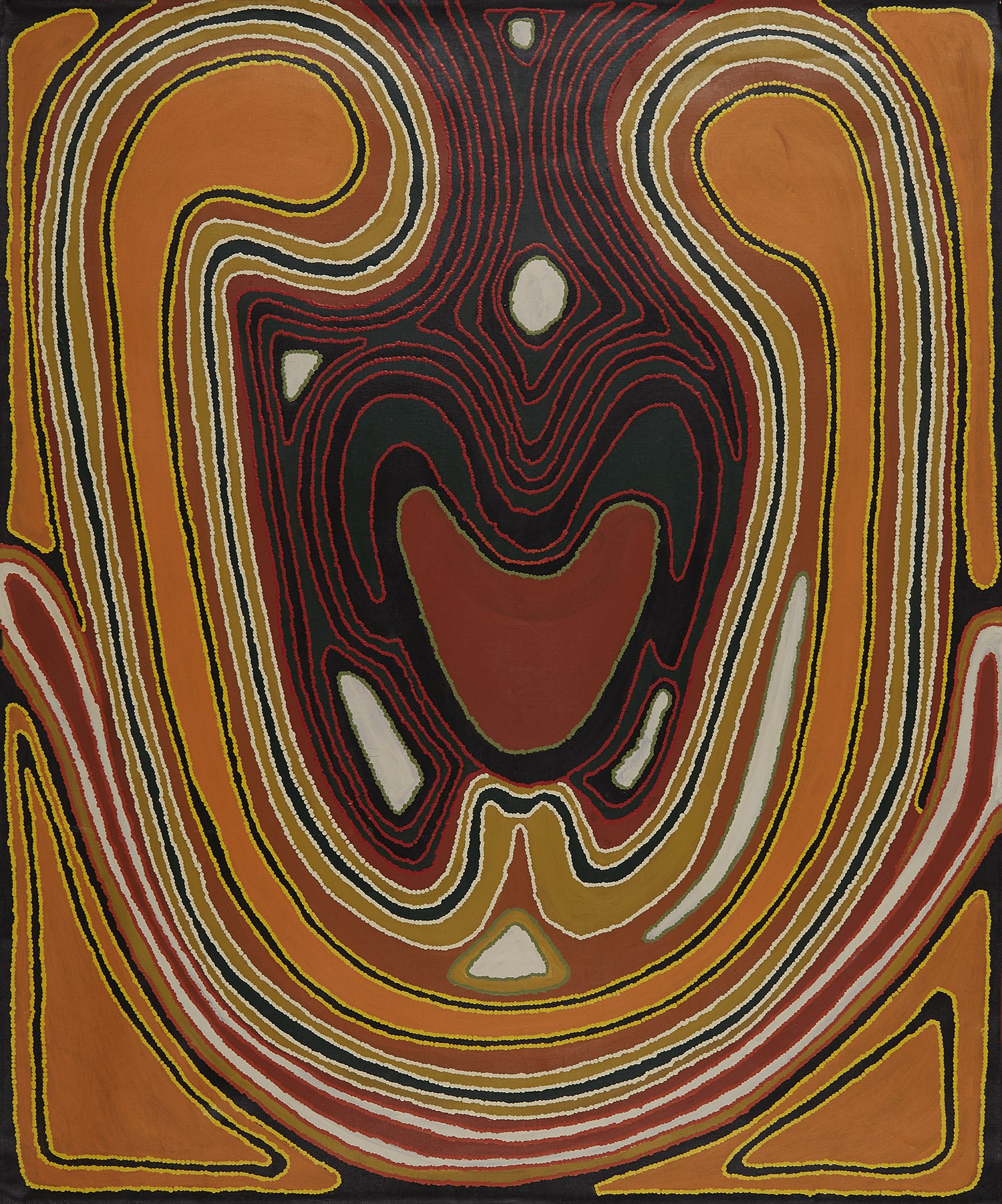

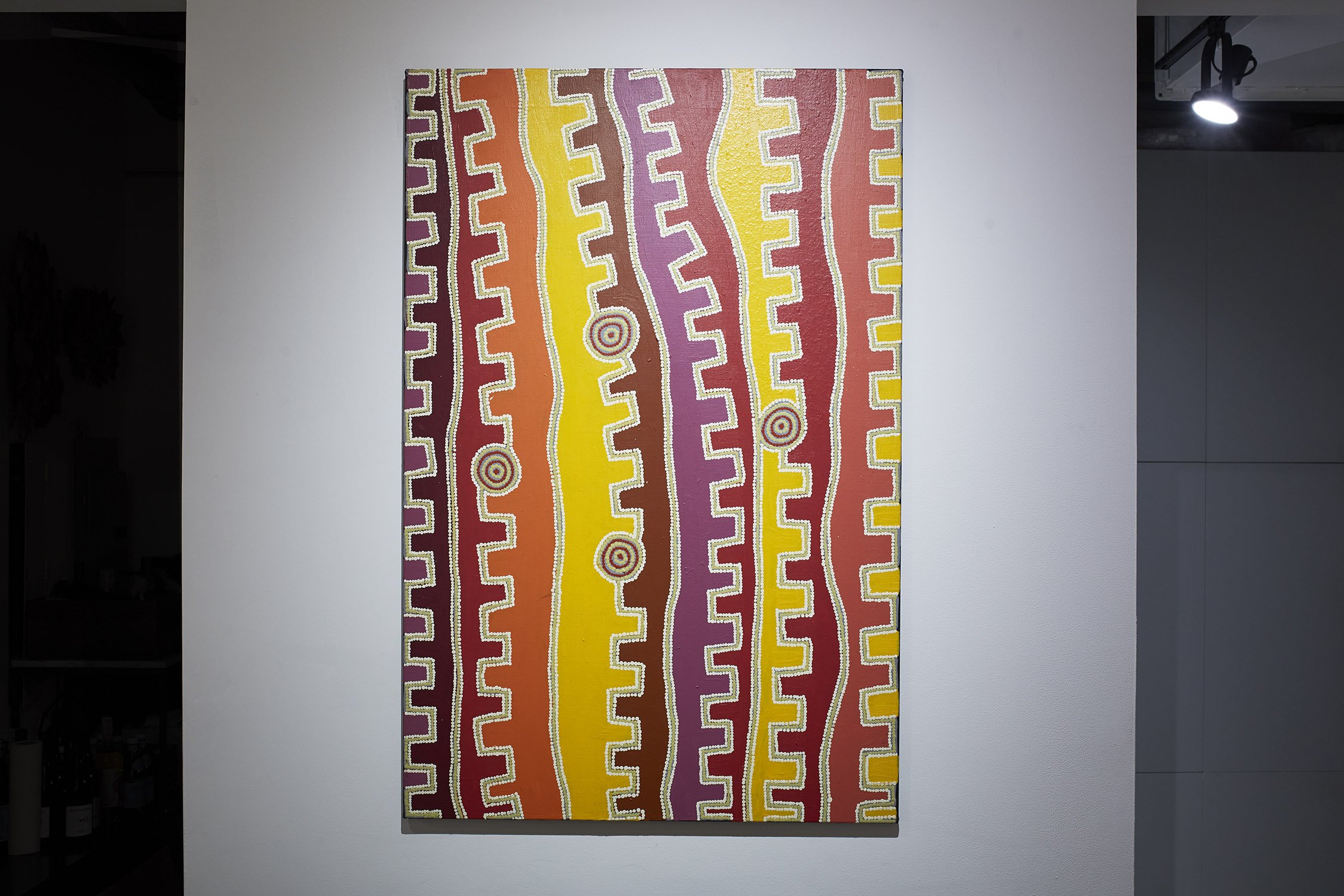

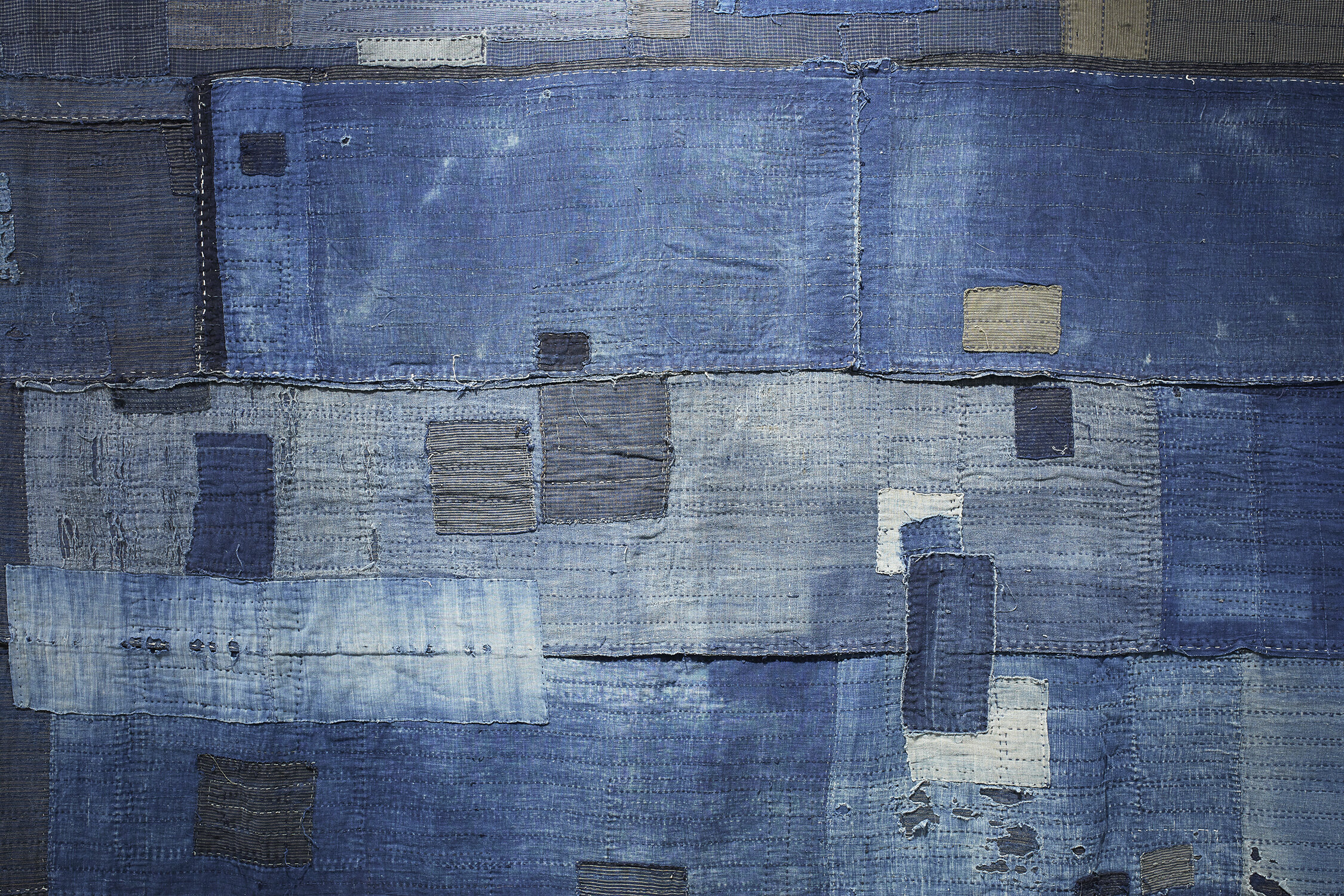

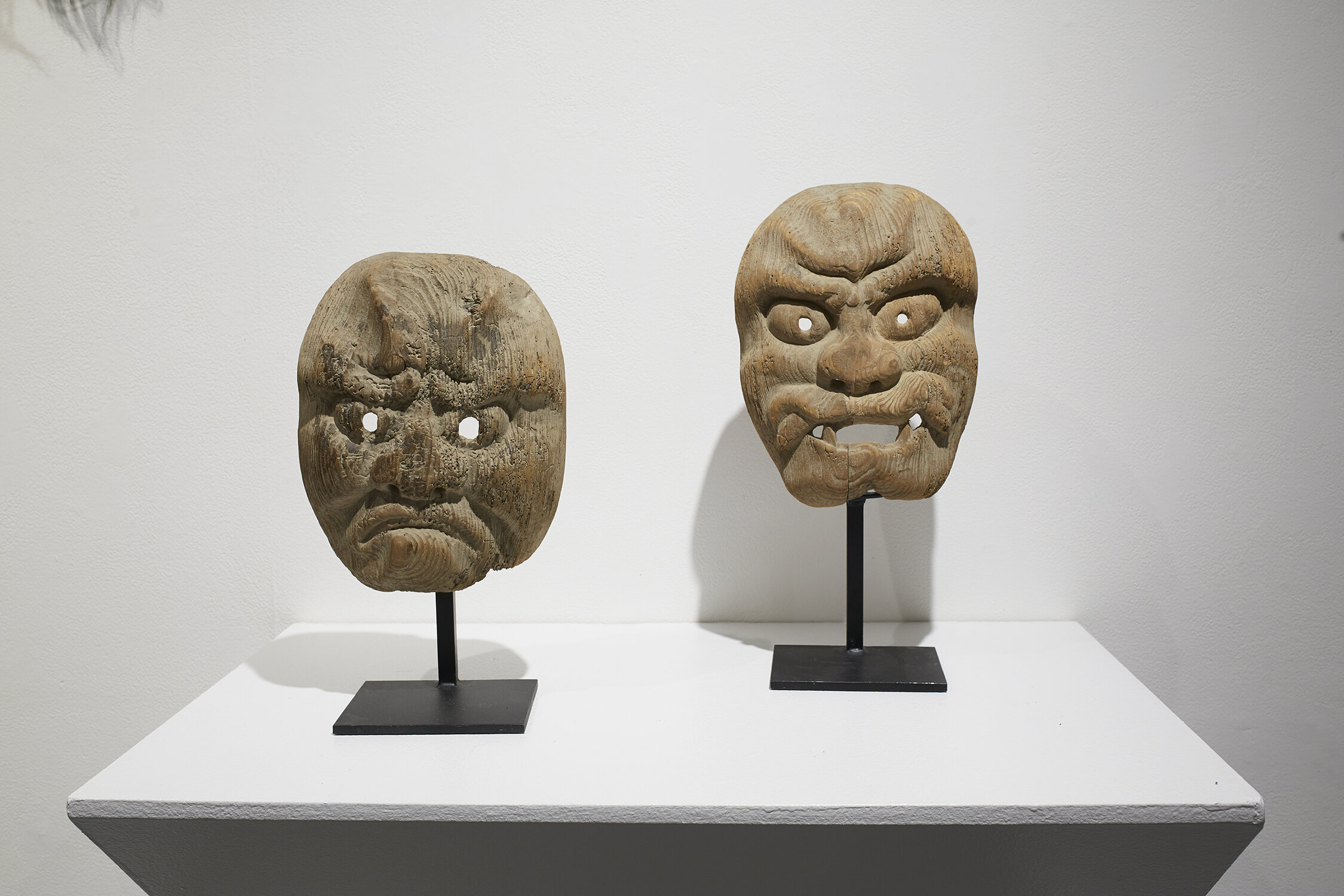

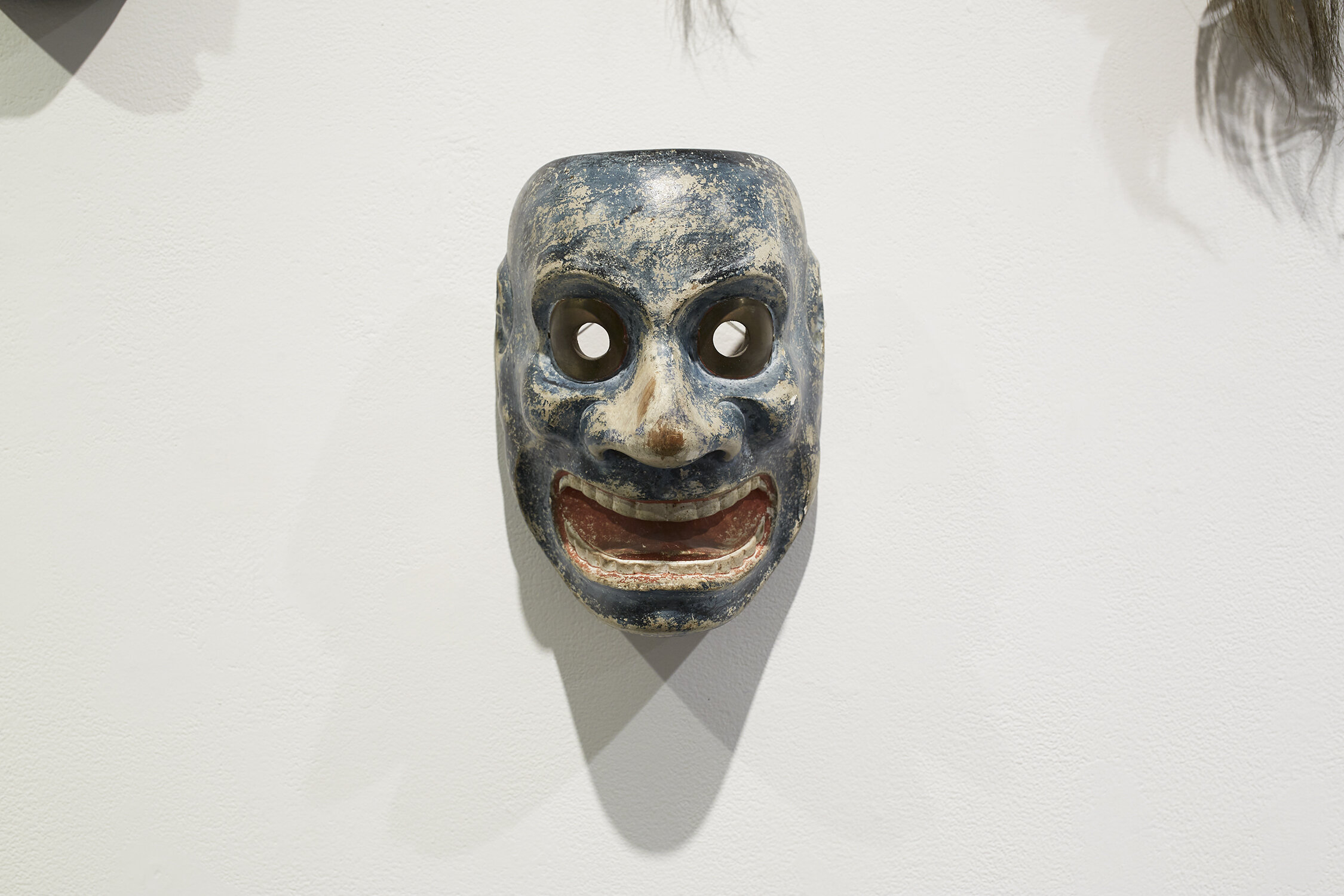

Shari was fascinated by the indigenous arts of Australia and the Native American art of the NorthWest Coast. I was coming to it from Haiti, Africa and Pre-Columbian America. We got a job together in an Indonesian craft import store which also had some major tribal textiles. We got to see how major collectors looked at this work, most notably Jeffrey Holmgren and Anita Spertus. Reading about those textiles from Sumba, Flores, Timor, Borneo, and Sumatra, as well as high end batiks from Java and Bali were really where our eyes were first seriously trained. We were completely immersed in those cultures, and our library was continuing to grow instead of our wardrobes. That reading was as far as it went to that point. We spent weekends at MOMA and the Met and in each others presences.

We danced around and with and in between each other. We merged areas of interest to discuss them better. It was an amazing time of learning for learning sake with no other motivations. I wasn’t into watching sports, we didn't have a TV that got more than one channel and even that was sporadic so we fed ourselves art. I left the phone sales job and tried to make it playing flute on the corner of 53rd and Fifth Avenue. Van Morrisons Moondance. Flute thing by Jethro Tull. Comin Home Baby. Summertime. Till one day my father walked by dropped a five dollar bill in my cup and walked away. That killed that. Shari began to dance with the Kenneth King Dance Company. We made earrings from wire and beads and tried to sell them. I was writing. The Indonesian job centered us just a bit.

It changed things. We thought we wanted to try it. Selling art. So we could travel and collect it. But not with Indonesian. We wanted to start with Haitian. If we could save or raise some money we could go to Haiti, bring back paintings of higher quality by lesser known or unknown painters, put them up for auction at Sothebys PB 84, which had been selling Haitian Art for years, and use that money to diversify a bit and upgrade and do it again. It was a flawless plan. The problem was it was a flawless plan in a flawed universe.

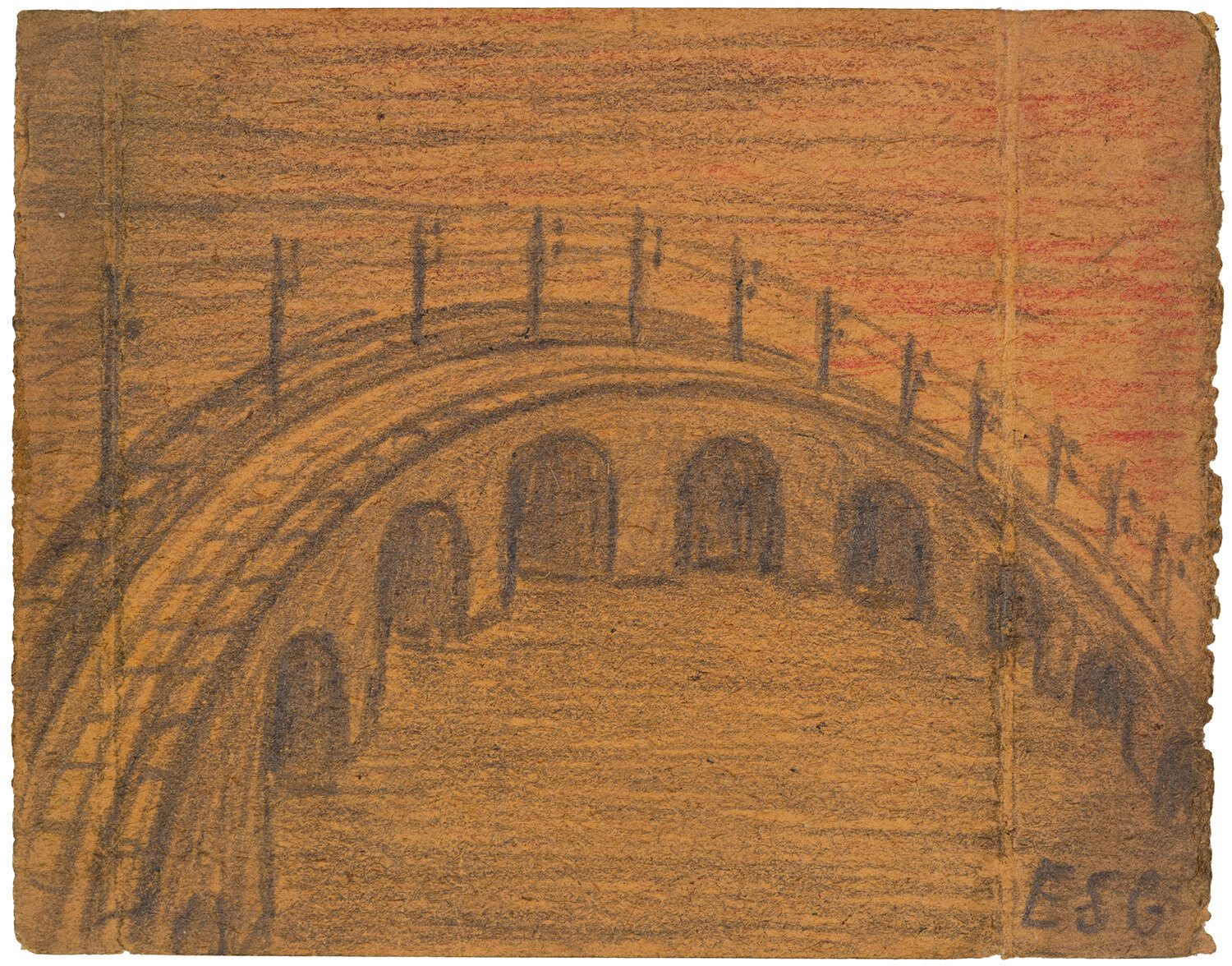

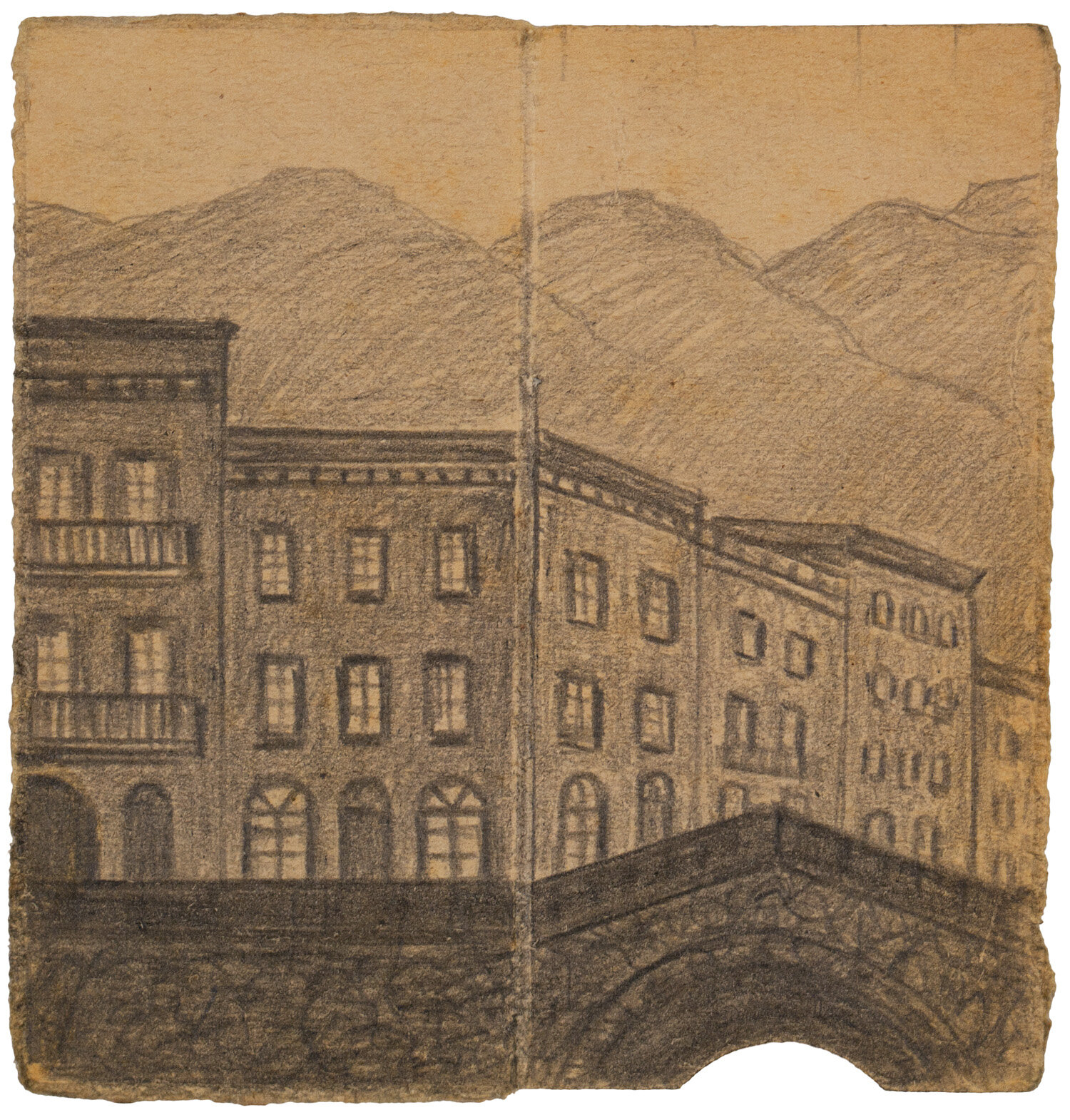

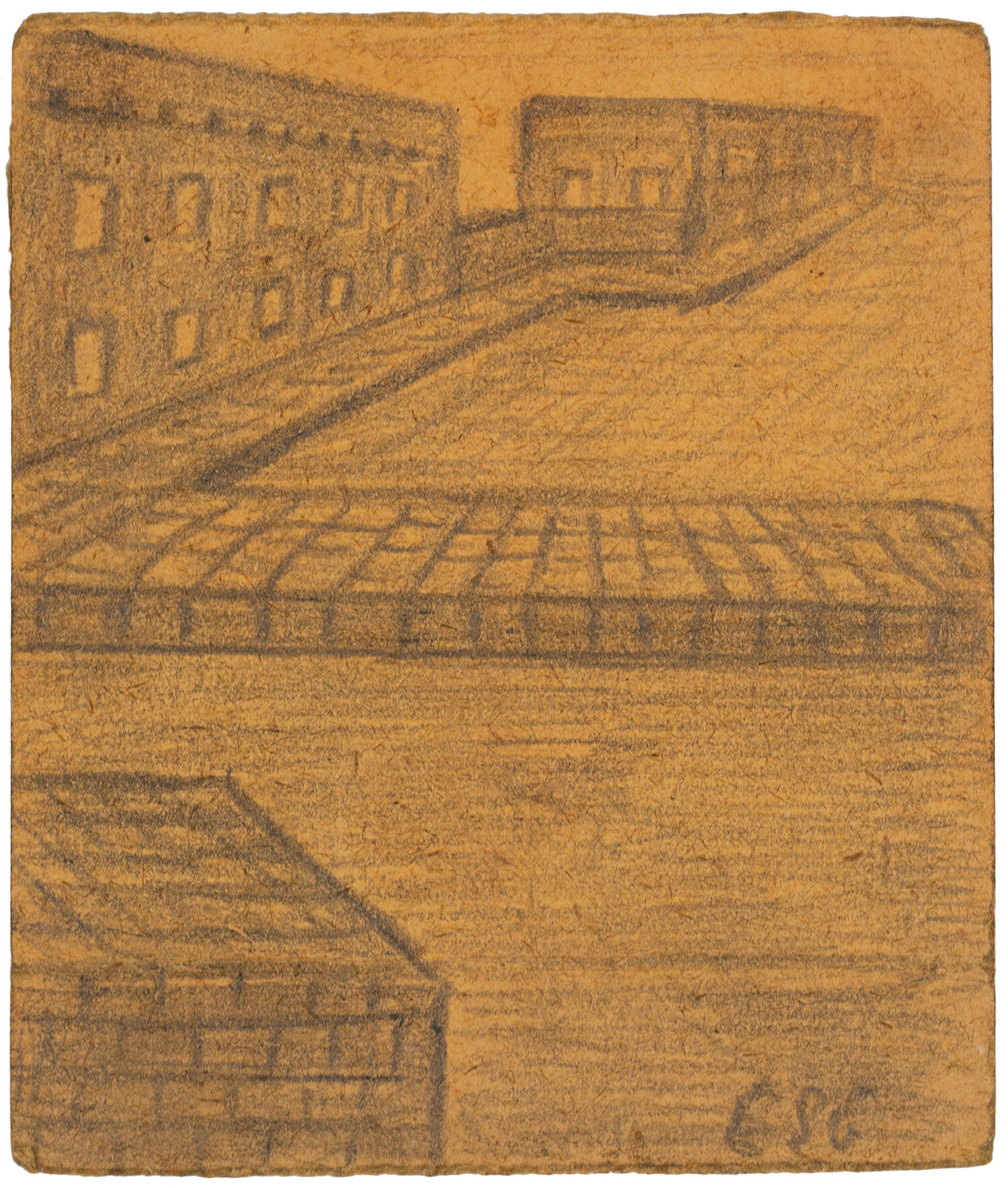

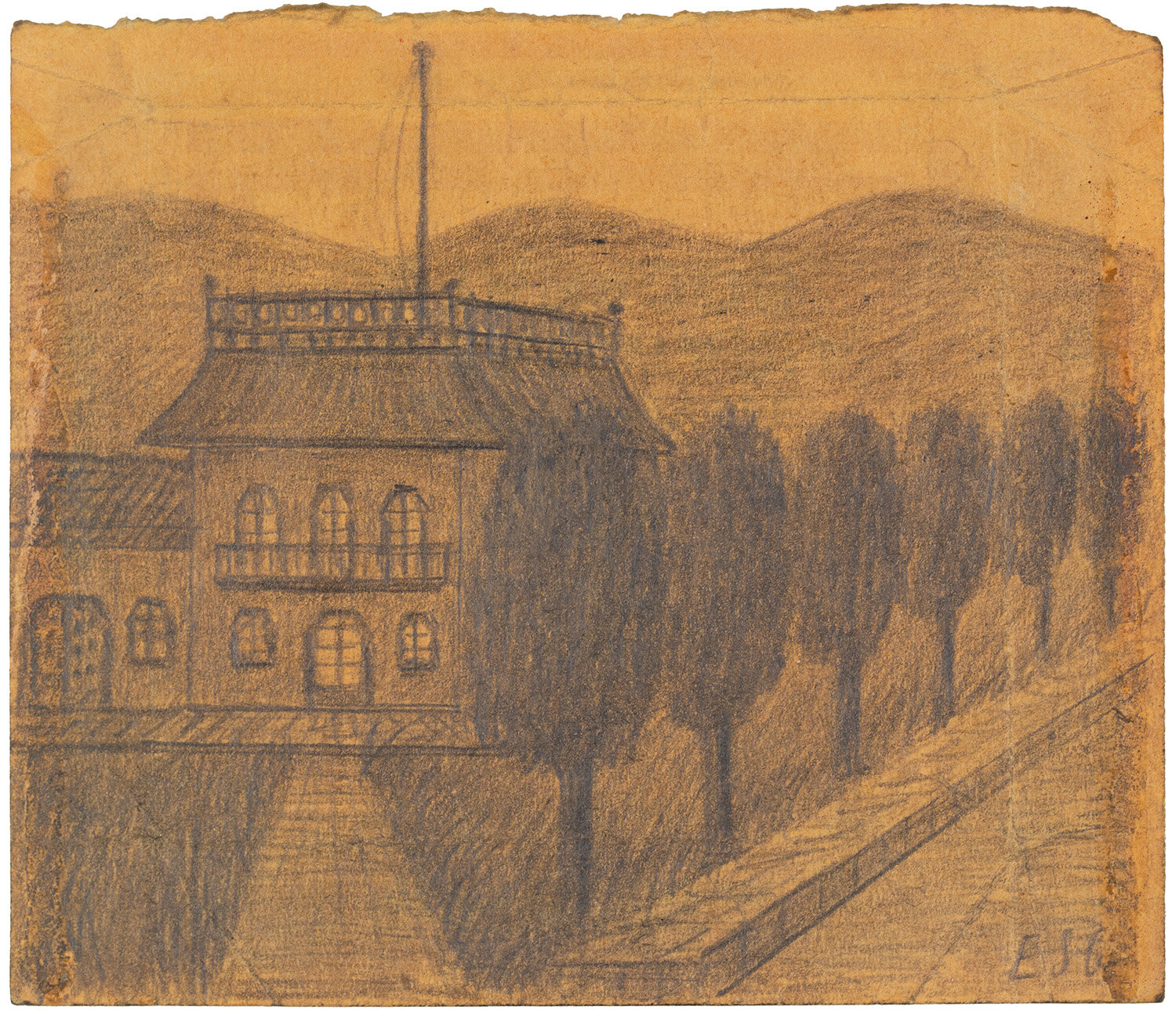

Why Haitian art for us? Oddly enough it was something we never questioned. In my case it was something that was simply always there. I had grown up seeing it and hearing about it. Reading about it opened a world for us we were completely comfortable in. The art was direct and mysterious at the same time, the same way great poetry or music is mysterious. It seems endless. It shapeshifts. I think of those two simple Hyppolites my father owned; how their presence was a chord chiming through my life. One was a landscape of St. Marc where the artist lived, as seen from the sea, the way a fisherman would view it on returning home each day. I used to stare at it as a child feeling the way the naked sun would kiss the white tiny white houses disappearing up a breast-like green hill. there was so much hidden life in that painting. And I knew some day it would be mine. It would be, along with its companion, a bond between my father’s vision and mine.

The other Hyppolite painting was a sacred still life flushed with the deep red and ethereal flowers that signified the presence of the lwa of female eroticism, Erzuli. Because of those paintings I read about the art, the religion and what was then written, mostly by Seldon Rodman, about this artist, Hector Hyppolite who was a Vodou priest who learned his style from painting temple walls and who so obviously and deeply and poetically loved women. These paintings will be yours, will be yours, yours……..I loved them and the villagescape from 1947 by Andre Lafontant, a cock fight, and lastly a graceful beautiful Ascension from the same time by Denis Vergin that many thought was actually painted by the master Castera Bazile.

Things did not turn out as expected. I did not turn out as my father expected. He did not really approve of the woman I was to marry and so , to make some point I never quite understood he sold the Hyppolites to a collector in Washington and gave me the other paintings. I was not at my wisest. I was so furious about the Hyppolites I sold two of the other paintings to my eternal chagrin to a well known private collection and kept the Lafontant which my eyes fall on whenever I look up from writing this. True, they were minor Hyppolites as Hyppolites go but they were repositories of family memory for me.

A year later they were stolen from the collection in Washington DC and never seen again.

I met Rodman in Haiti when I went with my father. They were both old lefties and it was sometimes grueling to be near their conversations as they out leftied each other. But Rodman was the literary man. I went back to New York and read his books as did Shari later on. I didn’t always agree with his takes on indigenous Haitian culture especially Vodou even back then with what little I knew about it but I liked his books for their positive and almost elegiac reverence for the way the Haitian self-taught artists, once noticed by the Centre d’Art and a small public, just effloresced in a steady illumination of creativity and expression.

During the post-war 1940s, and not only in Haiti but in Jamaica and the United States as well, different groups of well-intentioned people began to notice the art of untrained artists. These people, coming from the framework of Modernist sensibilities, were aware also of the presence of this art called ‘Naïve’ or “Primitive” in Europe. They were aware of the American aspects of this art in books like Sidney Janis’ “ They taught Themselves” and they were aware of Horace Pippins’ socially concerned and narrative paintings. Rodman was later to write a small book on the paintings of Horace Pippin. A lot of attention in the Caribbean was placed on the work of Henri Rousseau, not the least because of his lush jungle settings.

I have more words now for what I didn’t have words for then. Back then we just did it instinctively, relying on our own marital sense of checks and balances. Of course in retrospect I am a more sure of this process of building a mutual eye. We both knew what constituted mainstream beauty and neither of us was afraid of seeing powerful art that was not mainstream as its own form of beauty. This we learned from looking in other cultures.

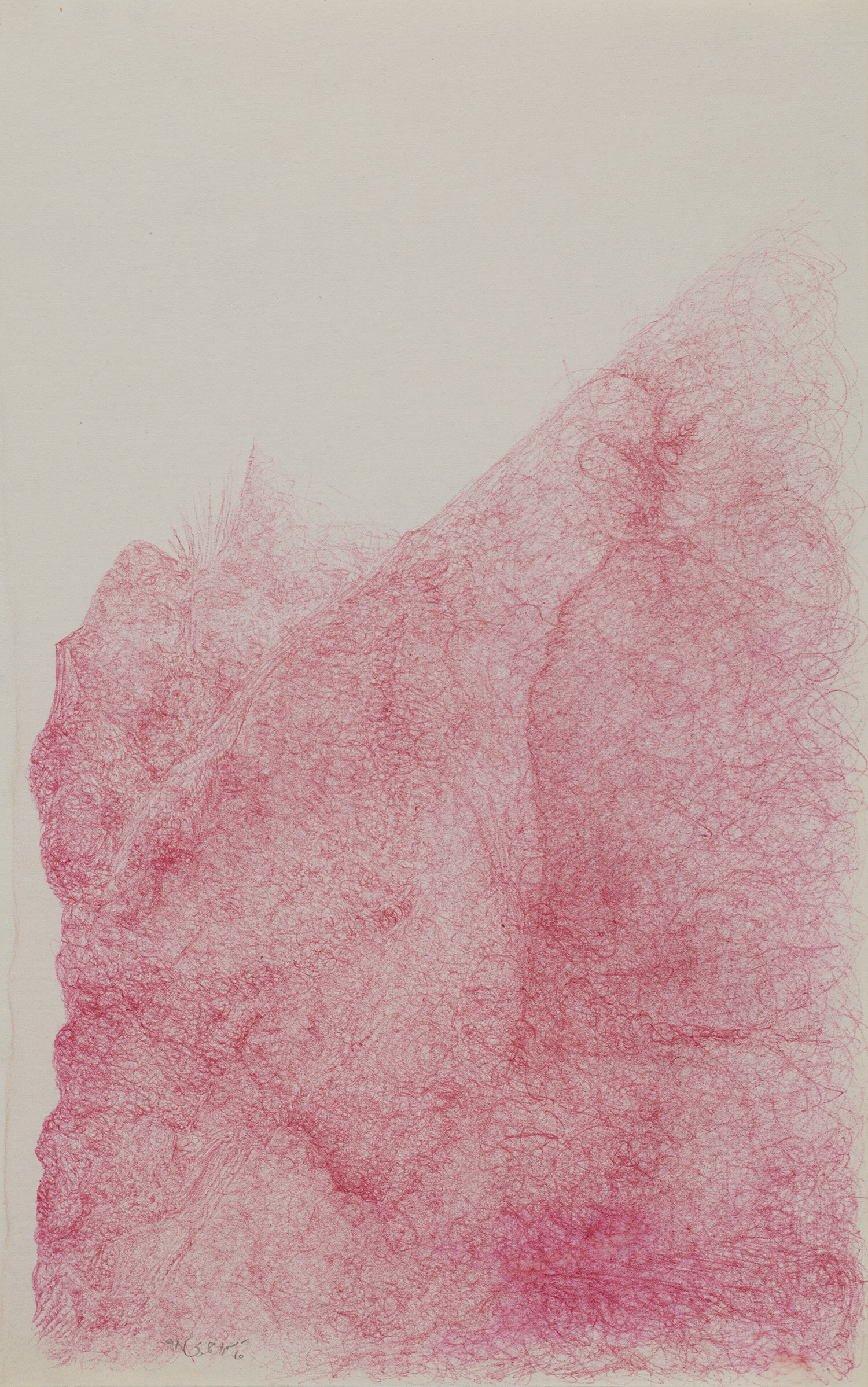

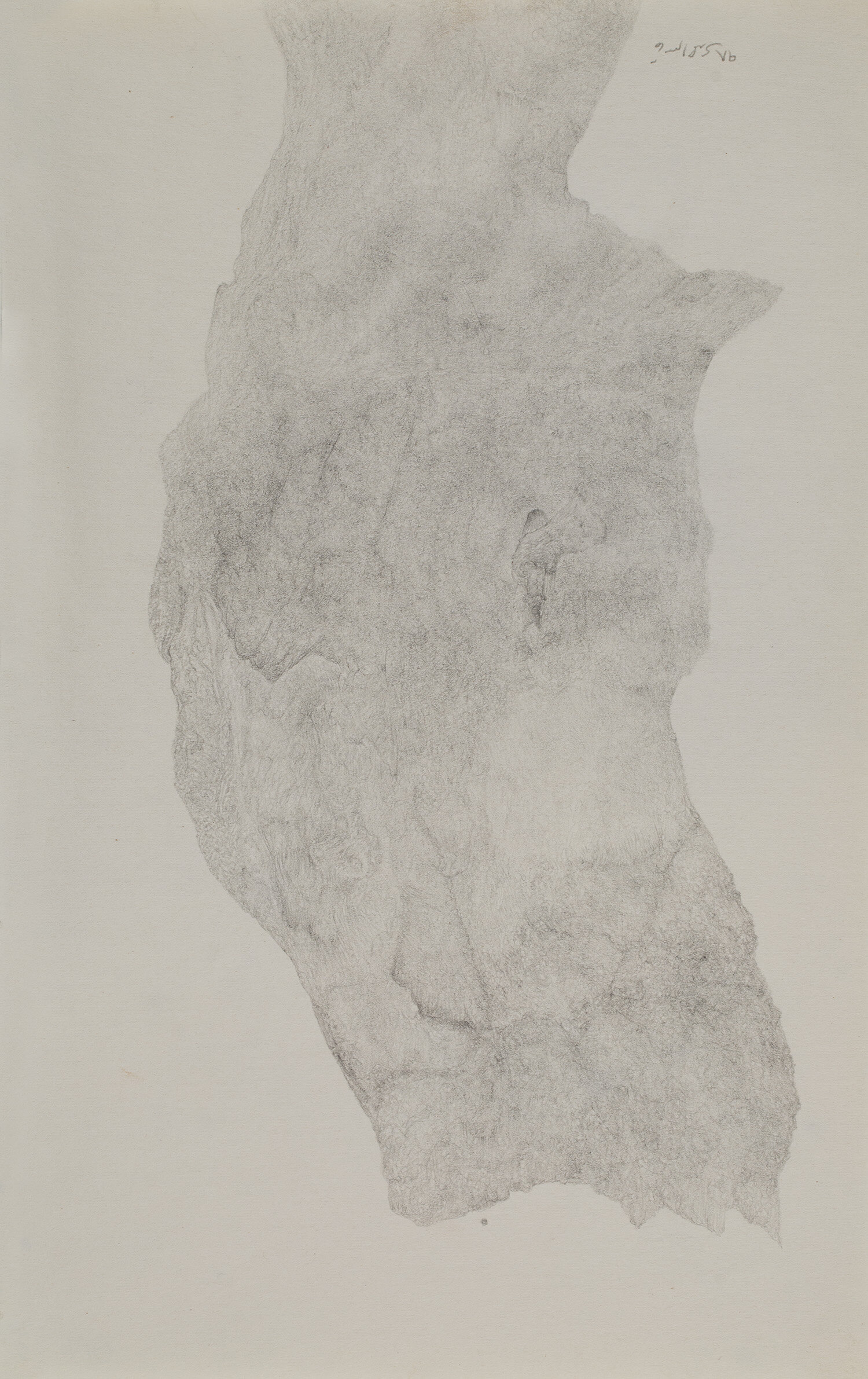

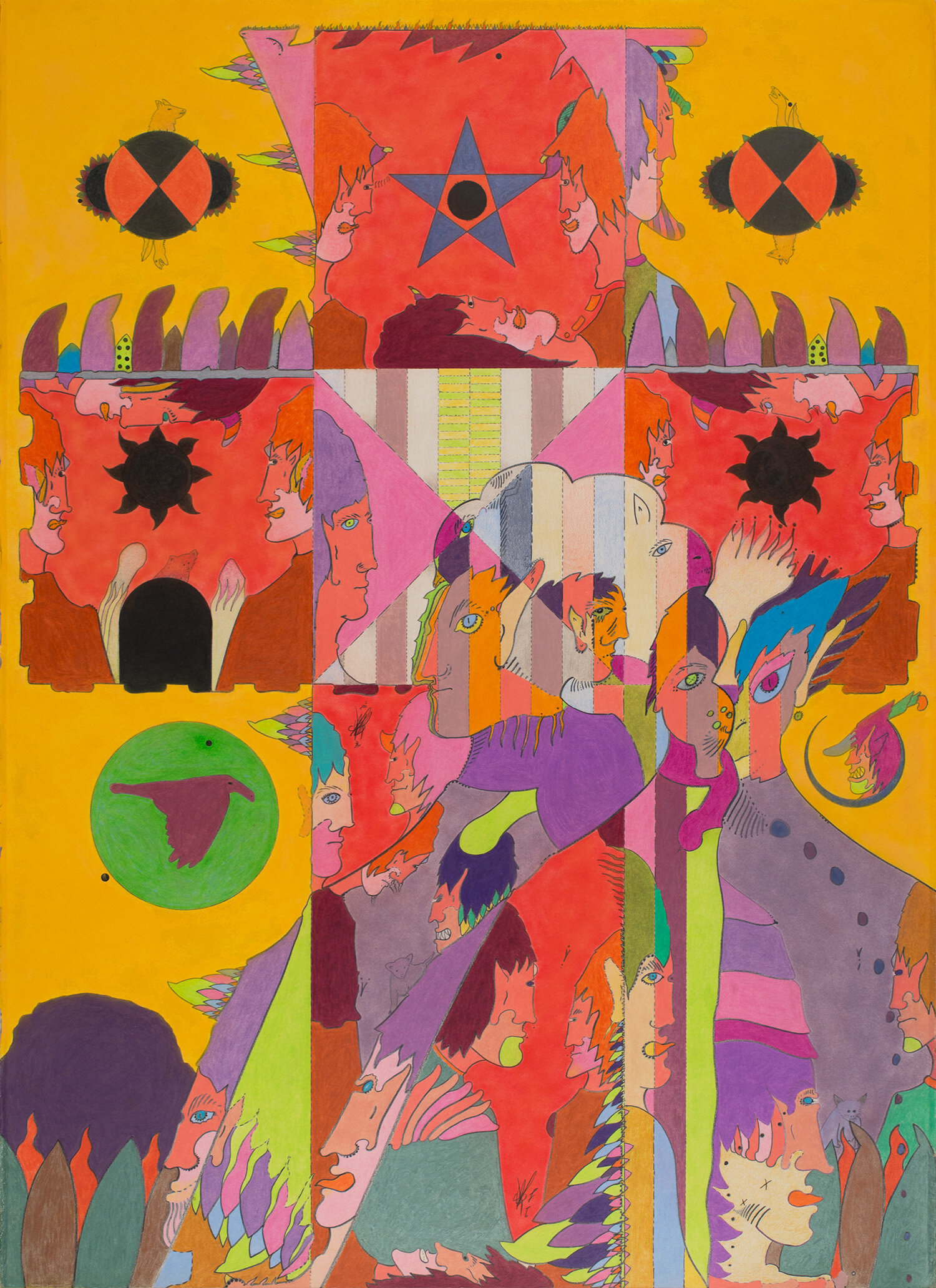

And for us beauty was very much a part of Haitian culture but it was not artificially separated from its aesthetic of power. We were attracted to the artists who drew from their own lifeways rather than those who were encouraged by others to be more Rousseauesque. This has nothing to do with the quality of their work. It was our choice and we didn’t realize then how this very choice was crucial to what we were to become later.

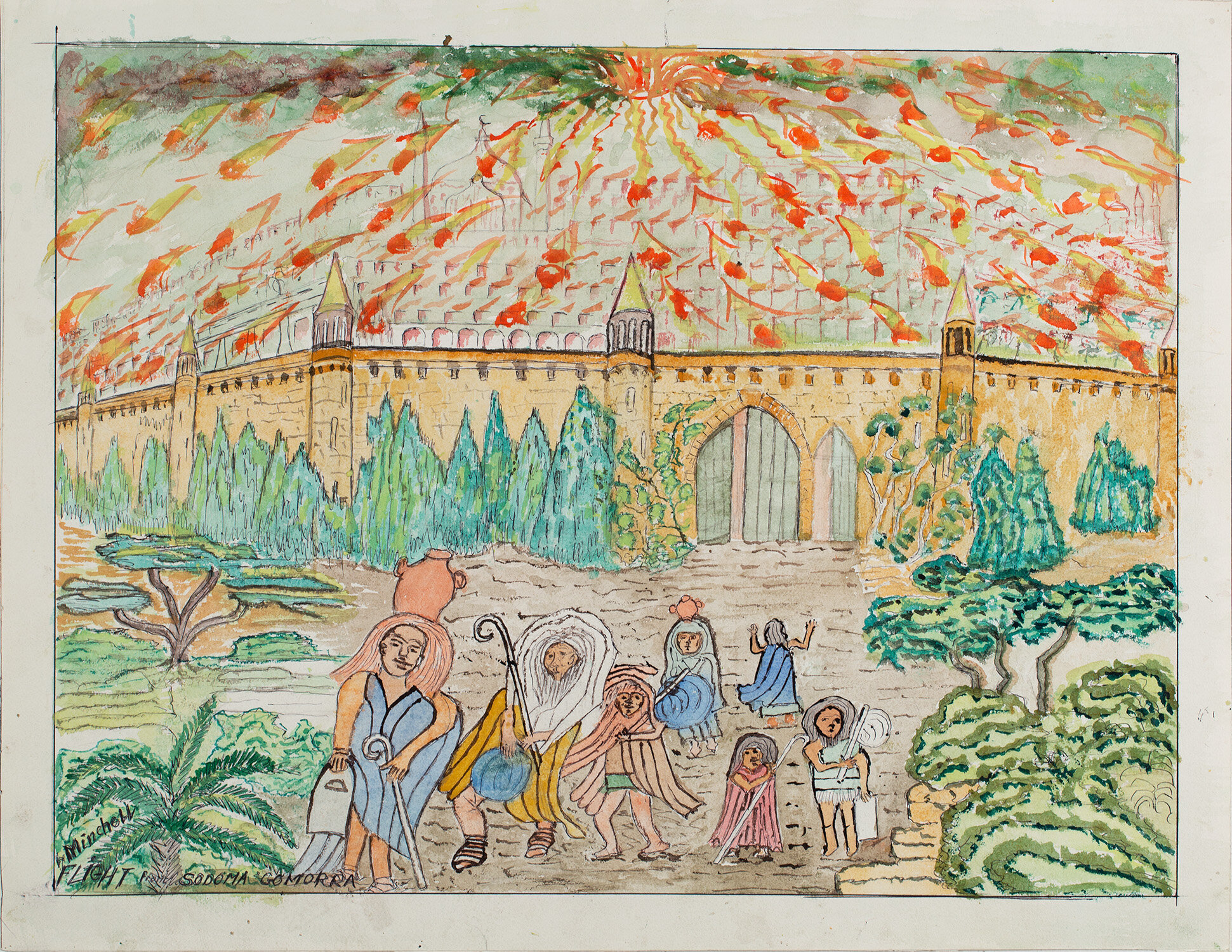

We were drawn to the religion of this country. We never meant to be Vodouissants but we wanted to learn because of the beautiful intricacies of its system, how it moved through the memories of existence, the infinite varieties of its historical and artistic accumulations. We understood the attractions of the first generation painters as well as anyone did but we also knew it was still going on; that, like its African counterparts in Benin and Togo and Central Africa, Haitian culture was not and is not static. Africa didn't freeze in a mid 19th C. aesthetic or political lifeway. It kept on going and growing. It was the same with Haiti, and coming later in our experience, with Jamaica and the Southern United States.

Indigenous aesthetics are always in flux. They are intertwined with racial and political urgency. They are always affected by what is global. They might seem decadent to an antiquarian or a purist but genius is genius, and fortunately for all of us is not confined to any particular era.

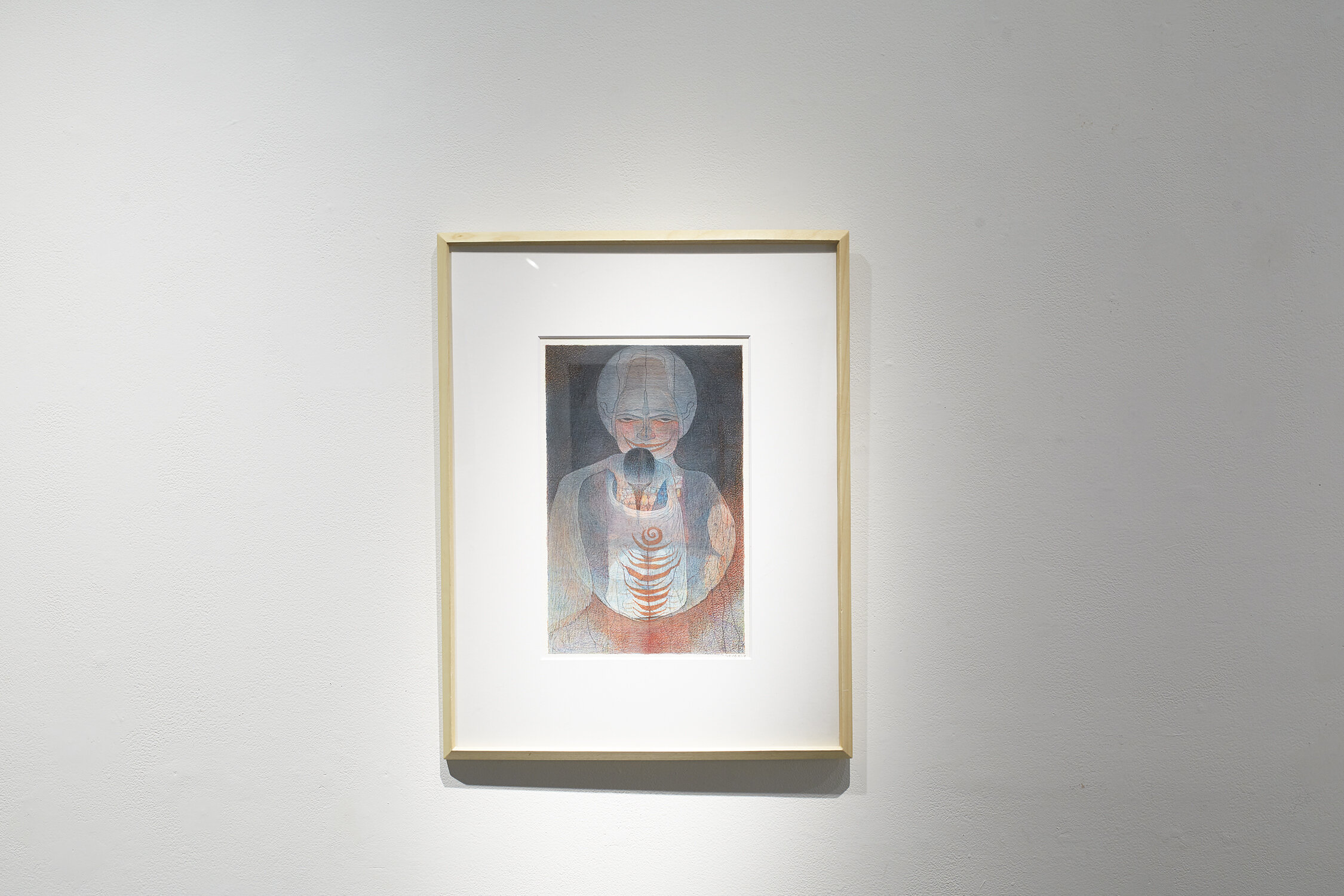

Haiti didn’t push us away. We found paintings by artists who appealed as storytellers and intertwined with those stories were deeply experiential observations of Vodou. We loved the work of artists who were actually priests and this reflected in their work; Andre Pierre, Robert St. Brice, Hector Hyppolite, LaFortune Felix etc. We saw artists like them who never put a brush to Masonite but who painted the walls of Vodou temples and other places of worship. It was connected to the Place….it drew meaning from Nature much like Shinto in Japan or animism in Nepal.